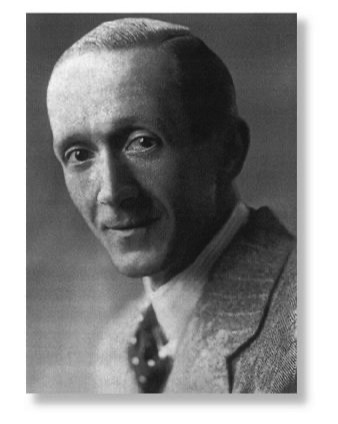

GILBERT TEW

The home of a Gasworks manager in Victorian England does not sound like a good literary background and how Gilbert Tew received an education that got him to Cambridge is not recorded. However, the fact that he was brought up on Robert Louis Stevenson, J. M. Barrie, Rider Haggard, G. A. Henty, O’Henry, and Kipling’s children’s stories, undoubtedly gave him a literary bent. He was also a great lover of Shakespeare (as had his father been), and could quote at length from the plays.

In 1903 Gilbert went from Warwick School to Emmanuel College Cambridge to read Classics, the first in his family to go to university. In 1904 he took the prize for Classics, and won a scholarship of £40 for 1904-5 and 1905-6.

Evidently he thoroughly enjoyed the Cambridge experience, which marked him for life. Small and slight, he was not good at sports, but he had exactly the right build for coxing the Emmanuel Boat. He became Secretary of the Debating Society, and then Vice President. When he took Tripos in 1906 he gained a creditable degree.

Gilbert’s attitude to social conventions was consistent with his family’s sturdy non-conformist tradition, proud and egalitarian and he stood his ground amongst the Cambridge elite. His sense of self-worth undoubtedly stood him in good stead for his career in the Indian Civil Service - a career that he chose, he said, so that he could fish for mahseer. He was to spend the whole of his working life in Burma (Myanmar), fishing whenever he could, but as it turned out the chances of fishing for mahseer were very limited in that country, and in that career, and he longed to return to England to fish for trout.

The essays in Being Fair to Trout had appeared in various country life and sporting journals between 1913 and 1946. Starting in Edwardian times, the period included World War I and World War II. The majority were written in his retirement, in the 1930s and 1940s. Some of them are escapist, evoking happy fishing holidays to forget the reality of war. They are also nostalgic, written during the winter after the fishing season is over, longing for the spring to come again, or written in the close season, longing for September. Or, written from Burma, they focus on his longing to be in England during the fishing season. Or later in life, the old man is looking back to the joys of his youth. He had some plans to publish them as a collection, but illness prevented him, so it was his daughter, the late Professor Mary Douglas, who brought them together, enhancing them with both a commentary and, as a separate chapter, her own anthropological study of the trout angler.

The home of a Gasworks manager in Victorian England does not sound like a good literary background and how Gilbert Tew received an education that got him to Cambridge is not recorded. However, the fact that he was brought up on Robert Louis Stevenson, J. M. Barrie, Rider Haggard, G. A. Henty, O’Henry, and Kipling’s children’s stories, undoubtedly gave him a literary bent. He was also a great lover of Shakespeare (as had his father been), and could quote at length from the plays.

In 1903 Gilbert went from Warwick School to Emmanuel College Cambridge to read Classics, the first in his family to go to university. In 1904 he took the prize for Classics, and won a scholarship of £40 for 1904-5 and 1905-6.

Evidently he thoroughly enjoyed the Cambridge experience, which marked him for life. Small and slight, he was not good at sports, but he had exactly the right build for coxing the Emmanuel Boat. He became Secretary of the Debating Society, and then Vice President. When he took Tripos in 1906 he gained a creditable degree.

Gilbert’s attitude to social conventions was consistent with his family’s sturdy non-conformist tradition, proud and egalitarian and he stood his ground amongst the Cambridge elite. His sense of self-worth undoubtedly stood him in good stead for his career in the Indian Civil Service - a career that he chose, he said, so that he could fish for mahseer. He was to spend the whole of his working life in Burma (Myanmar), fishing whenever he could, but as it turned out the chances of fishing for mahseer were very limited in that country, and in that career, and he longed to return to England to fish for trout.

The essays in Being Fair to Trout had appeared in various country life and sporting journals between 1913 and 1946. Starting in Edwardian times, the period included World War I and World War II. The majority were written in his retirement, in the 1930s and 1940s. Some of them are escapist, evoking happy fishing holidays to forget the reality of war. They are also nostalgic, written during the winter after the fishing season is over, longing for the spring to come again, or written in the close season, longing for September. Or, written from Burma, they focus on his longing to be in England during the fishing season. Or later in life, the old man is looking back to the joys of his youth. He had some plans to publish them as a collection, but illness prevented him, so it was his daughter, the late Professor Mary Douglas, who brought them together, enhancing them with both a commentary and, as a separate chapter, her own anthropological study of the trout angler.